💡 This Essay is part 1/2 of my series on loneliness.

Read part 2 here!Table of Contents:

Introduction

The Loneliness Epidemic

Studies

Key Points

Takeaways

Ways we try (and fail) to find belonging

Building belonging

Introduction

Last September I set out on a mission.1

After a year of moving to new places and grappling with feeling lonely in various ways and for various reasons, I decided to dedicate some serious time and effort to investigating the loneliness epidemic, the attention-grabbing topic of a report released by the U.S. Surgeon General in 2023. This report was the first time I had found big-picture data to back up the pervasive (and seemingly worsening) mass loneliness I’ve been observing and absorbing from the environments around me for the past 7 years.

I started studying loneliness by gathering statistics, reading reports, watching documentaries, scrolling through reddit and youtube comment sections, and listening as people shared their life stories.

I then chased real-world experiences of my own: leaving my comfort zone and moving to different cities, paying attention to if I felt lonely (and why), searching for belonging everywhere from running groups to networking events to dating apps to Taylor Swift dance parties.

Dealing with loneliness in different contexts and on different timelines was an amazing (and difficult) learning experience — sometimes I’d feel that I’d found belonging the second I entered a new environment, and sometimes no matter how hard I tried, I could not successfully make a place feel like home. Experiencing different outcomes in different environments led to the beginning of my hypothesis that loneliness, though often internalized as a personal problem, is often imposed upon us by the design of our environments.

And with that belief, I’ve been putting my learning to the test by ✨“World-Building”✨ — learning through trial and error how to design environments that help strangers connect meaningfully with each other in real life. Having outlets to put my learning to the test has allowed me to fine-tune my gut feelings about where loneliness comes from and experiment with creating a version of the world where we’re all a bit less lonely.

After 12 long months of focus (and many years of doing this work without realizing it), Part 1 of this essay is my best attempt to consolidate the most important things I’ve learned about the problem, while Part 2 (Loneliness: The Four Circles of Belonging) is an extremely tactical troubleshooting framework that I hope sparks ideas for those who (like me) have struggled with loneliness and need a little bit of help figuring out how to get from wherever you are now and where you’d like to be.

The Loneliness Epidemic

Studies:

Some of the most clear, comprehensive studies I’ve read about loneliness:

Loneliness Matters: A Theoretical and Empirical Review of Consequences and Mechanisms, Louise C. Hawkley, Ph.D., John T. Cacioppo, Ph.D.

Loneliness across time and space, Maike Luhmann, Susanne Buecker & Marilena Rüsberg

Loneliness is a feminist issue, Elanor Wilkinson

Key Points:

Loneliness is “an unpleasant emotional response to perceived isolation”. Notably, loneliness is not the same thing as solitude. It is very possible — and very common — to feel lonely when surrounded by others, and equally possible to be completely content while in isolation.

This trend started before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Popular depictions of the ‘loneliness epidemic’ frequently speculate on the conditions that might have resulted in a rise in loneliness, such as family breakdown and technological shifts, but they often fail to give space to other far more integral causes of social isolation, such as the restructuring of the labour market, the rise in zero hours contracts, mounting housing insecurity, family separation as a result of a hostile immigration policy, the violence of racial capitalism and the securitisation and privatisation of public space, all of which limit our capacity for connection. - Loneliness is a feminist issueLoneliness has severe consequences on individual health.

It is making us die faster.Loneliness and social isolation increase the risk for premature death by 26% and 29% respectively. More broadly, lacking social connection can increase the risk for premature death as much as smoking up to 15 cigarettes a day. In addition, poor or insufficient social connection is associated with increased risk of disease, including a 29% increased risk of heart disease and a 32% increased risk of stroke. Furthermore, it is associated with increased risk for anxiety, depression, and dementia. - Our Epidemic of Loneliness and IsolationLoneliness ALSO has profound impacts on the health of our communities and institutions. Society is deeply dysfunctional when we don’t feel connected.

Social isolation among older adults alone accounts for an estimated $6.7 billion in excess Medicare spending annually... beyond direct health care spending, loneliness and isolation are associated with lower academic achievement, and worse performance at work. In the U.S., stress-related absenteeism attributed to loneliness costs employers an estimated $154 billion annually. - Our Epidemic of Loneliness and IsolationYoung people are feeling the most lonely.

Loneliness is a common experience; as many as 80% of those under 18 years of age and 40% of adults over 65 years of age report being lonely at least sometimes, with levels of loneliness gradually diminishing through the middle adult years, and then increasing in old age (i.e., ≥70 years). - Loneliness Matters

Takeaways:

As with all important problems, it’s easy to find data and statistics to discount the lived experiences of real people. Some say the problem isn’t that bad, that I should be grateful I didn’t live in *insert another time period here*, say other people have tried and failed before (so what am I realistically going to do about it), and deny the problem is even real.

As with all important problems, it’s even easier to find data and statistics to tell us just how doomed we all are, alongside fingers that point at who and what are to blame for the impossible situation we’ve found ourselves in. My biggest beef with everything I’ve ever read about loneliness is that it’s incredibly pessimistic — humans are really really awesome at problem identification, and not always that great at at imagining or implementing effective solutions. A search for “Solutions to loneliness” yields a long list of suggestions that are valid but also some combination of obvious, inaccessible, or for lack of a better word… cringe. Maybe I’m just a hater, but tips like “try self-care” and “find a hobby” feel condescending and don’t inspire me to take action.

Finally, as with all important problems, at some point you have to go with your gut, stop reading theories, get out of the problem identification phase, and start doing first-hand, trial-and-error research in the real world.

These two essays (and the work I’m going to be doing for the next several years) rests on the foundation that whether or not it can be classified as an epidemic, loneliness is a real problem, it’s an important problem, it has severe cascading consequences both individually and collectively, millions of people are trying and failing to cure their loneliness, and the problem is not yet solved. These points are all supported by a lot of data, but on a deeper level, I know these statements to be true because I see it around me every single day.

In the real world, when I tell people I’m working on loneliness they pause.

They listen.

On several occasions, I’ve been looked at right in the eyes and told with deep sincerity that I need to keep doing this work. People check in for status updates, ask to be my first customer, offer their time and skills, and are ready to support the cause however they can. In the real world, I don’t need statistics to convince people this loneliness thing is real. They feel it too.

One last thing that I’ll state before I get into the main part of this essay — after a year of research, I fundamentally believe that the loneliness epidemic, like all problems, is something we can address. There is no shortage of people to meaningfully connect with, and everyday people have the power to cure loneliness for themselves and for each other.

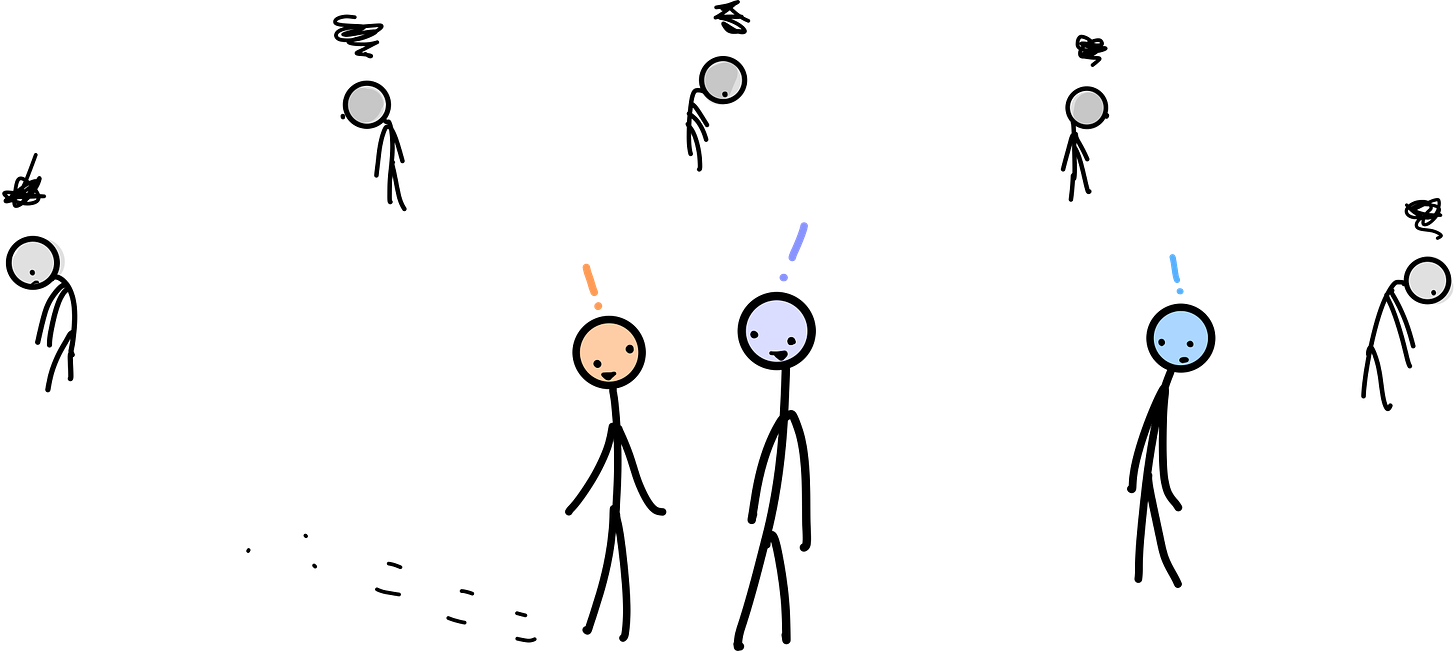

Ways we try (and fail) to find belonging

The opposite of loneliness is belonging. To add some colour to impersonal statistics about shortened life expectancies and economic losses, it’s helpful to imagine a world where the void is filled — what might it feel like to live in a world where it’s easy to feel like you belong?

Belonging is the feeling of being truly seen — not just for who you present yourself as on the surface, not just because you possess a useful set of skills or resources, but for your quirks and intricacies and flaws, for the things that keep you up at night, for the things that make you laugh, and for the person you dream of becoming. It’s the feeling that you matter.

Mild loneliness helps spur us into action, but chronic loneliness is self-reinforcing (Negative interactions with others will make you feel more lonely, causing you to approach future interactions with hesitation and perceive the actions of others as more threatening, meaning your interactions will be more negative, reinforcing your belief that others are unwelcoming, making it harder for you to experience positive social interactions…) and can spread contagiously through communities like a disease (Interacting with someone who perceives you as hostile will likely be a negative social interaction for you, making you act more guarded in future social interactions, causing others to have negative social interactions with you, meaning they will be more guarded in their next social interactions…).

The dissonance of being surrounded by people but feeling deeply alone finds a way to taint all of your social interactions. After repeated failed attempts to find meaningful connection, most of us come to one of three unhelpful (somewhat crushing) conclusions:

“There is something wrong with me”

This stems from the belief that belonging must be earned.

There are massive industries that benefit a lot from convincing people that solo self-improvement (going to therapy, reading self-help books, mindfulness podcasts, gymfluencers, jobs that pay well, educational institutions, etc. etc.) is the key to finding belonging, connection, and friendship. These things are not bad, but when self-improvement takes a turn for the obsessive, it’s time to turn to the words of Rayne Fisher-Quann:Your job is not to lock the doors and chisel at yourself like a marble statue in the darkness until you feel quantifiably worthy of the world outside. Your job, really, is to find people who love you for reasons you hardly understand, and to love them back, and to try as hard as you can to make it all easier for each other. - Rayne Fisher-Quann,no good aloneUnfortunately, so long as belonging is conditional on maintaining a highly-curated image of yourself, you’ll find yourself standing at the edge of chatter-filled rooms, watching people laugh in slow motion at unfunny jokes, wondering if you’ll ever be able to shake the hollow, unsettled feeling of not being surrounded by “your people”. The alternative — having no one — seems like a far worse option, so you’ll cling to a curated persona and you’ll stew and analyze and wrack your brain for solutions: after all, belonging is an irreducible need of all humans, and loneliness, like hunger, drives us to seek what we need for survival.

“There is something wrong with the people around me“

This stems from the belief that belonging must be found.

Uprooting your life and leaving everyone you know behind in order to “find your people” feels extreme, but many people I know have ended up at this conclusion.

It may very well be the case that “your people” are not in the place you currently live, but not everyone is capable of taking such extreme action, and in my experience, moving far away from home for 4 months taught me just how much I took for granted — being in the same time zone as your parents, having someone to call when you’re sick, and knowing that someone would notice if you didn’t show up to work or school or wherever-it-is is underrated.“There is no hope.”

Feeling like you will never belong can be really scary. It usually leads to doing nothing and retreating into ourselves, questioning how the hell anyone else figured out how to make real friends, thinking that we’ve missed our chance, hypothesizing that maybe everyone else just got lucky but wondering if maybe they’re all just pretending too.

Earning belonging, finding belonging, and giving up cannot possibly be the best 3 strategies we have — so what are we supposed to do?

Building Belonging

I’ve learned that people who make other people feel like they belong are not born, they’re raised. If loneliness is contagious, belonging can be too.

Anyone can learn how to do this, and if you give it an honest try, you’ll find that believing in and celebrating the people around you is the cheat code for being believed in and celebrated. Time and time again I’ve seen hosts gain the most belonging in the communities they curate — because they act as if it’s their duty to make others feel welcome, that energy is constantly being reflected right back at them and contributing to their positive spiral. Beyond this, I think extending a branch into your network to someone who is feeling socially isolated (often when moving to a new place) is one of the most meaningful things you can do — something that costs you almost nothing (e.g. an invitation to a party) gives them a starting point that can make and break their entire experience of the place they live. Though I’ve extended invites before without a second thought, I could not have possibly understood how impactful they were until I moved somewhere new and struggled for months to make even a single friend.

The awesome thing about the loneliness problem is that we’re not blocked by anything — there’s no shortage of natural resources, specialized tools, or need for lots of startup funding. We all have more power than we think we do, and we already know how to do this — even if we feel awkward and confused and out of practice, it’s comforting to remember that underneath all of these layers of anxiety and distraction, humans are hardwired for connection.

In my life today, people are already taking control of their lives and pulling belonging out of thin air — through sheer willpower and determination, they’re coming together to build the world they want to be part of.

We are all. right. here.

💡 This concludes part 1. Up next, read part 2 -- Loneliness: The Four Circles of Belonging. (dramatic, but not clickbait.)

seriously enjoyed reading this! what app do you use for the drawings?

It has gotten to the point where I cannot even play a regular video game without feeling lonely. I find myself playing MMORPGs literally just to feel the souls connected to the avatars on the screen pass my character by.

A great and well-timed piece for me, thank you for the reminder that it's down to me to build a world I feel I belong to.