Sensitivity-to-the-world

A non-psychologist's take on 'giftedness', ADHD, and how the storytelling surrounding sensitivity determines whether it's perceived as an 'obstacle-to-overcome' or a 'superpower-to-be-harnessed.'

This essay is part 1/2. Check out part 2 when you're done!Official Labels & Diagnoses 🧠🔥

I was diagnosed with ‘giftedness’ as a kid.

I’ve always hated the term. If you’ve been taught to value humility, getting diagnosed as ‘gifted’ feels pretentious, comes with a “duty to live up to your potential”, and adds friction to the already-difficult process of getting accommodations for the very real and specific set of struggles1 you’re likely to face — after all, why should we make life even easier for ‘gifted’ people… isn’t ‘giftedness’ already an unfair advantage?

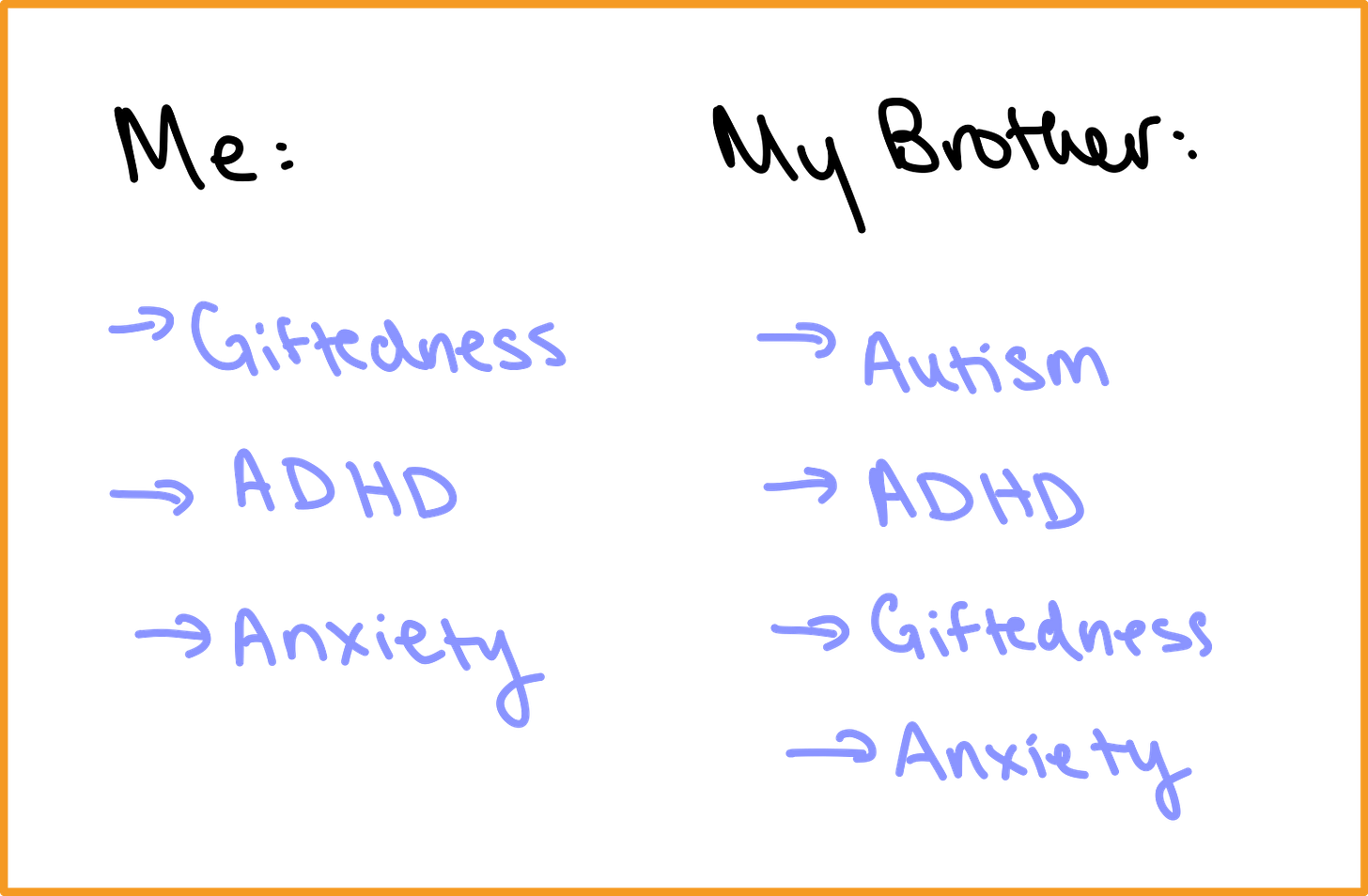

Around the same time, my brother was diagnosed with Sensory Processing Issues, Giftedness, Asperger’s Syndrome (later renamed ‘high-functioning Autism’), followed by an ADHD diagnosis, then Anxiety. I’ve always hated the consequences of some of these other labels too — they evoke an emotional reaction somewhere in the land of pity-awkwardness-confusion-sympathy, none of which feel like the right response.

For those who meet my brother after knowing about these diagnoses, there’s usually some sort of (well-intentioned) expression of disbelief as they recalibrate their expectations — ‘I never would have known, he’s so intelligent, articulate, and funny!’. And they’re right, he is. Probably one of the most intelligent, articulate, and funny people I know — our collective perception of “what people with these diagnoses are like” is definitely off. For people who meet him before knowing about the stuff he has a harder time with, his witty commentary and extensive knowledge (about pretty much everything) sometimes make them less understanding — it’s always seemed that if his struggles were more visible, people would be more eager to provide accommodation.

This phenomenon isn’t unique to my brother — it seems that when we struggle, there’s a ‘threshold of suffering’ that needs to be hit to have our needs taken seriously (by others, but also by ourselves). Having a triage system seems to be the fairest way to distribute limited resources — we put out urgent fires, and we help people when they’ve given ‘sufficient proof of pain’. But this system has a really obvious flaw: no one asks for help until they’re completely falling apart, and climbing back to a good place is infinitely more difficult when you’re at the bottom of a downward spiral than when you’re just beginning to slip.

If we could articulate our needs before they became dire and urgent (or better yet, if our environments were designed to address them proactively), simple solutions might reduce a lot of suffering.

Because of this, I’m a big fan of subtle, catch-all inclusion efforts.2 Just because your struggle isn’t visible, doesn’t mean it’s not real. Being accommodating by default (and not making people explain themselves or prove the extent of their pain to ‘earn’ accommodations) feels like both the right thing to do and a lot less to keep track of.

That being said, I usually struggle to apply the understanding and accommodation I give to others to myself. After 21 years of ‘toughing it out’ and ‘I’m fine, my struggles aren’t bad enough to warrant doing anything’, I got diagnosed with ADHD too. I also sought therapy for some Anxiety problems I was dealing with.

At this point, the sibling scoreboard is looking something like this:

If you’re starting to think that the diagnoses are getting a bit out of hand and maybe we should just stop going to psychologists, maybe you’re right. 🤡

But I know it’s not just us. Critics are suspicious of the recent and dramatic rise in the percentage of the population diagnosed with ADHD, Autism, and Anxiety, but I think something else is up. People are visibly struggling more than they used to, and I know they’re not exaggerating because I see it around me every day. More on this later.

ADHD & Me <3

The classic ADHD trope is the hyperactive-11-year-old-boy-who-can’t-sit-still-in-class. Because of that, it never occurred to me that things I was struggling with fell under the ADHD umbrella until coming to university — for the first time ever, I had an audience of friends and roommates witnessing the elaborate behind-the-scenes coping mechanisms I’ve always used to keep up with life.3

As open-minded as I thought I was about the label, that was when it was other people’s ADHD — I didn’t need accommodation. I was fine, I had always been fine.

But then I spent some time on the internet. I got comfortable saying “so true” and chuckling at internet blogs titled “Living with adult ADHD as a 25-year-old woman”, and for an entire school term (Fall 2023), I decided to let the at-this-point-i’m-pretty-sure-I-have-ADHD take the wheel.

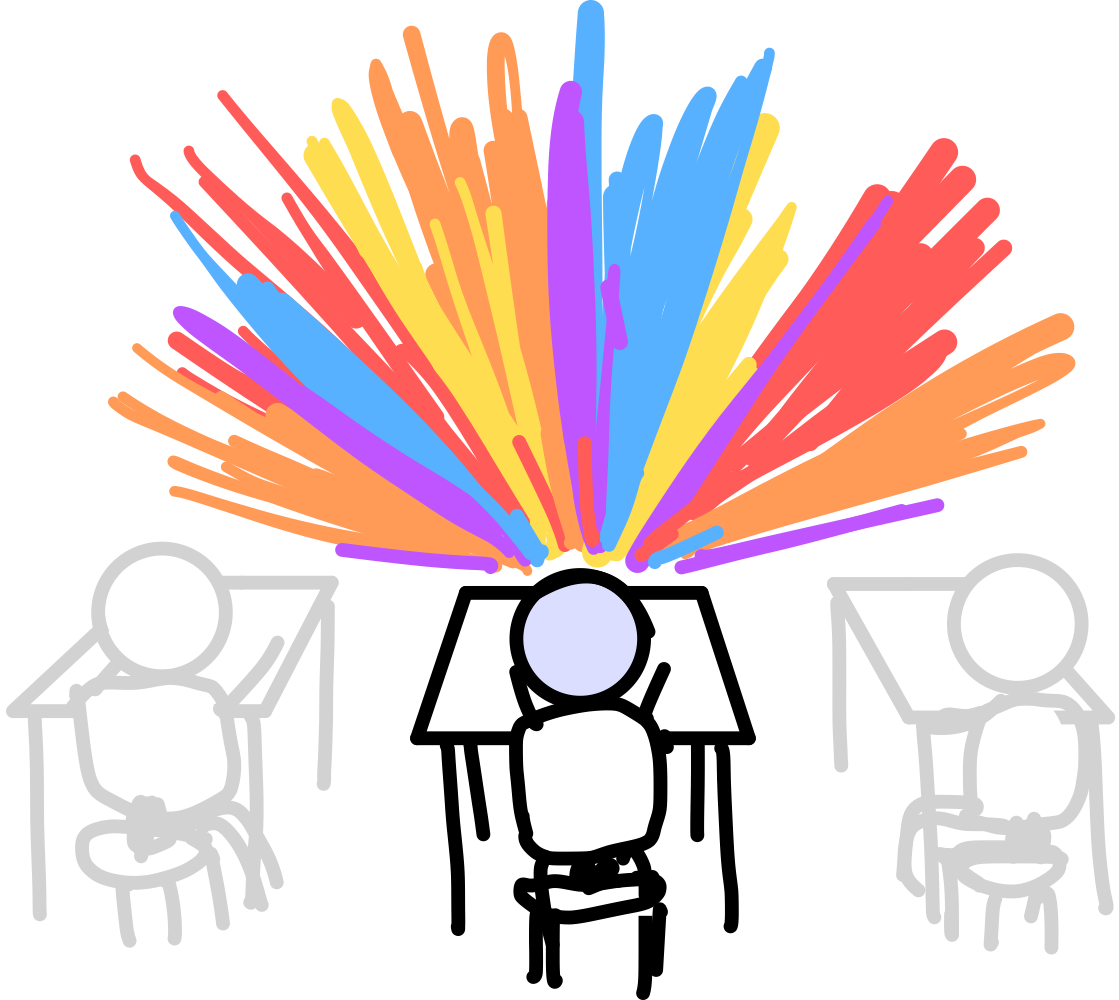

This meant leaning into wherever my energy took me (regardless of what I was actually supposed to be doing), but this time doing it with intention. This strategy… kind of worked? I felt lighter and happier — once I stopped resisting, I was able to reclaim a lot of the daily effort that was spent trying to forcibly wrangle my brain to focus on the task at hand. Instead, I used a variety of strategies (e.g. ‘going to class A so I could ignore it in the background while reading the lectures of class B, and vice versa ’) to do the best I could with the energy I had in any given moment.

At this point I still never intended to seek accommodation or medication — I didn’t want to have an unfair advantage over classmates, and I did NOT want to be dependent on a drug to be functional. But then I started to dream — of a world where *maybe* I could cook an egg from start to finish without forgetting I was cooking the egg. Maybe instead of doodling, reading lectures from other classes, and answering 15+ emails to stay awake during class, I could just… listen. The thing I wanted more than anything was to feel like myself when in my apartment or at home with my parents — for as long as I can remember, any time I’ve entered these less-stimulating environments, I'd be hit with a huge wave of drowsiness and fall asleep without fail, at any time of day.

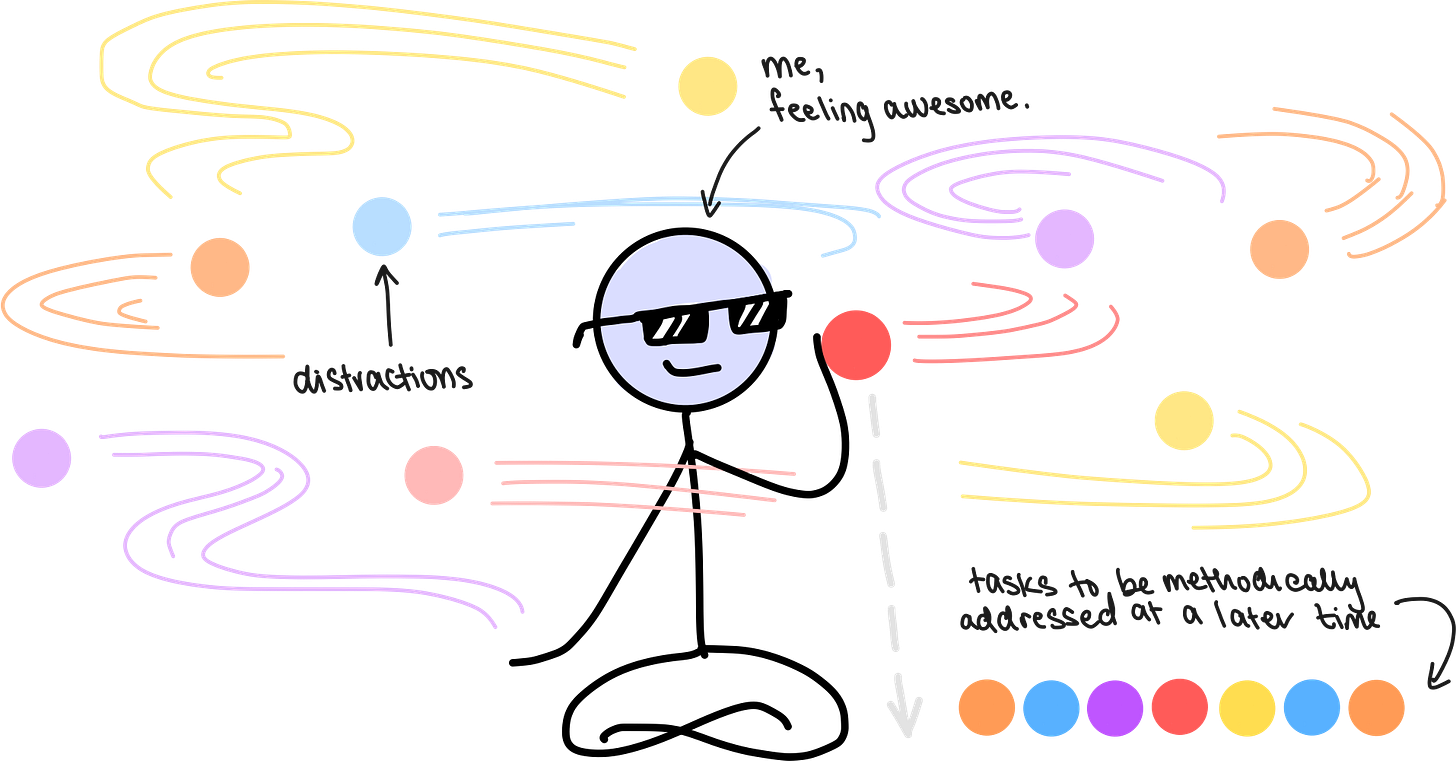

After sitting through my first lecture on an extremely low dose of medication, I looked down at my notes and realized they weren’t half-complete and covered with doodles. My eyelids weren’t heavy, and I didn’t get sidetracked 5 minutes into the lecture. Once it went quiet, I realized that the reason I hummed incessantly for 21 years was because I had both an internal monologue and an internal song playing in my head during all waking hours. I called my parents and sobbed — I could imagine a whole life ahead of me where I could set a plan and then do the plan, catching distractions hurled my way and consciously placing them aside to be methodically addressed at a later time.

To this day, I feel most like myself when I grab breakfast on my way out the door & come home only when I’m ready to sleep — meaning I’m typically out of the house from around 9 am to 11 pm. Despite this, medication has upgraded my bedroom from a glorified storage facility to a place where I can occasionally actually hang out. The exhaustion and energy slumps that come from constantly fighting my brain are now less aggressive, and I can usually make it through the day without a daily nap 😎.

I was worried that on medication I might stop feeling like myself, but I actually feel more like myself than ever before4— the now-definitely-diagnosed-ADHD has been demoted from the driver’s seat and I am at the wheel 😎. It’s still there, providing colourful backseat-driver commentary, but now I can turn around and say “hey! let’s play the quiet game”.

While observing me spend 7+ hours completely dialled into editing a video or an essay still tends to be alarming for friends and roommates, I’m now aware of the time passing and I’m making a conscious decision to keep going (not necessarily healthy, but nice! 🤡). I feel a sense of peace knowing that moments of true focus won’t be rare and fleeting — I can choose to take a break from work and come back to it later, and don’t fear letting a golden 4 a.m. opportunity slip through my fingers5. Tomorrow will be another day.

Same symptoms, different stories 🤔💭

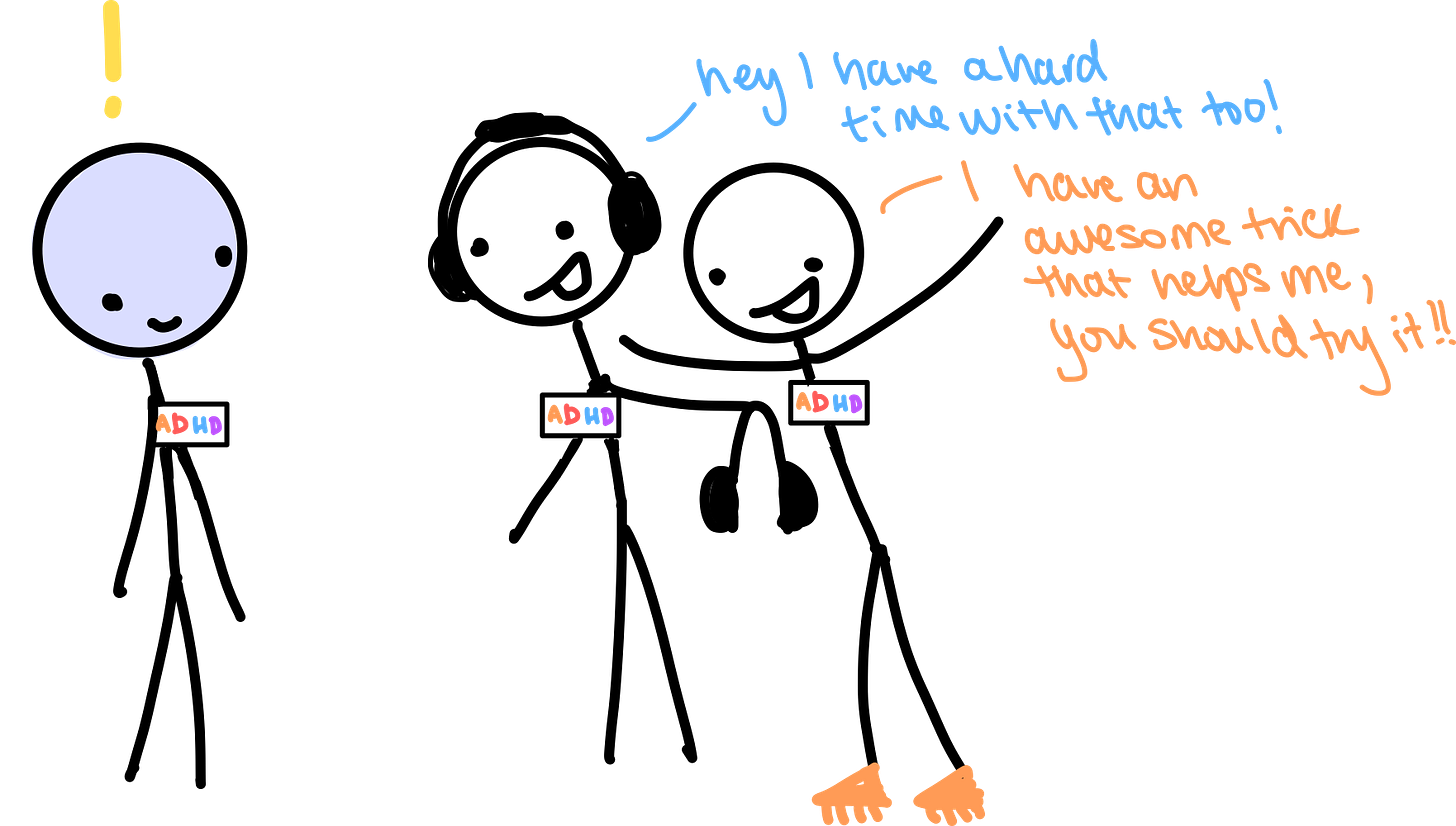

As we get older, my brother and I get better at articulating our experiences. More and more often, I hear him describing things I’ve felt but haven’t had the words for — he has a head start on me when it comes to accepting and understanding ADHD, and while I spent a lot of my early years trying to help him adapt to environments and overcome some of his obstacles, I now find that he’s the first one I want to call as I deal with mine.6 I can’t overstate how growing up with him has helped me (both proactively and retroactively) to deal with my own stuff.

As I realize how similar we are, it becomes increasingly absurd to me that I’ve lived a life labelled ‘gifted’ while my brother has been labelled as having ‘neurodevelopmental disorders’. Almost every intense, interesting, and successful person I know shows signs of adhd-giftedness-autism-anxiety-depression (whether it’s diagnosed or not). Clinically, the high rate of multiple diagnoses across these 'disorders' is called ‘co-morbidity’, but I’ve come to think of it as a spectrum that encompasses the question “How sensitive are you to the world around you?”

Too much of this conversation is often focused around the question of ‘how do we eliminate your sensitivity so we can make you more like everyone else?’, and not ‘how can we design environments and equip you with tools so you can channel your sensitivity productively?’.

Sensitivity cannot be separated from the hyperfixation and creativity that have resulted in some of the most important innovations we have today. While accommodations definitely help those with ADHD and Autism succeed in the world we live in (resulting in less anxiety and depression). I think ‘trying to find a cure’ would actually be a huge disservice to society.

‘Gifted’ is the story of someone with above-average-sensitivity that’s grown up in a well-designed environment and been equipped with tools to harness it.

Anxiety and depression are what happens when we fail to realize this.

A new story: the Sensitivity-to-the-world Scale.

I present the Sensitivity-to-the-world Scale.

Based on where you find yourself along the sensitivity scale, you may perceive the same environment very differently than someone else. You may be highly sensitive to the emotions of others, people talking, loud music, random interesting things on the street, rustling paper noises, flickering / too bright / too dim lighting, and itchy clothes. On the flip side, you might be sensitive to random intrusive thoughts and struggle in slow-paced environments because your brain decides to go off exploring on its own.

If you’re on the highly sensitive end of the scale, your Sensitivity Meter gets overloaded at a lower threshold, so to prevent overloading and having a meltdown you may have developed some strategies to turn down the “volume”. These typically fall into the buckets of blocking it out (noise cancelling headphones, closing your eyes, retreating to less stimulating environments, having alone time) or tuning it out (humming, fidgeting, listening to white noise, sitting in environments with background activity).

Under this framework, it becomes pretty easy to explain why “Everyone has ADHD these days” and “I think I have ADHD!” is a lot more common commentary than it used to be. We’re all working with the same sensitivity thresholds as we had 10, 100, and 1000 years ago, but in a very short window of time, we’ve had the volume (across every domain) cranked up. We’re not becoming more sensitive, the world is getting louder and more stimulating — it’s no surprise that more and more of us are cracking and dealing with the negative consequences of not having the tools to deal with environments that are not built for us anymore.

Official labels are still important.

So why don’t we all just use this Sensitivity-to-the-world Scale and forget about getting officially diagnosed? Labels spur a variety of emotions and perceptions that are often unhelpful, maybe we’d all be better off just solving our problems independently.

From what I’ve seen, there are two major reasons official diagnoses are important:

Understanding yourself through connecting with people like you

Articulating the environments7 and accommodations you need to be successful

In my opinion, those two reasons are significant enough to continue with labels.

That being said, I think reluctance around labelling ourselves in the name of ‘I’m fine, I don’t have a disability’ or ‘not wanting to have an unfair advantage’ etc. is a barrier that prevents a lot of people from learning about themselves, sharing their experiences, and exploring and articulating the environments and accommodations that could help them be the best versions of themselves.

I *hope* that introducing the Sensitivity-to-the-world Scale as an informal concept makes thinking about “what we need to be successful” (individually and collectively) less off-limits for people who are struggling to deal with the too-fast, too-loud, too-overwhelming world that we live in today.

There are a ton of tools out there (check out part 2 of this essay), and most importantly, you don’t need to have an official diagnosis to use them.

Take care of yourselves. <3

- Joss

Existential depression about the state of the world! All the time! (here are other things, this is just some random website among many, but you’ll get the gist).

I try to include stuff in the teams I lead (no hard feelings if for whatever reason you can’t get stuff done, just communicate early and ask for help!), and spaces I host (e.g. waiting 5 minutes for the last few stragglers to trickle into meetings). A slight loss of operational efficiency might be the one thing that keeps someone from breaking, and this feels worth it. I also appreciate win-win tactics like my physics professor’s policy of “48 hours of extension time that can be applied to any assignment all term, no questions asked” — this is accommodating to a variety of circumstances and reduces administrative headaches. Another example in the physical world is wheelchair-accessible design benefitting stroller users, people using carts to move heavy items, people with suitcases, people with other injuries, etc. I find when people oppose accommodations, they do so “in the name of ‘fairness’” — even when it makes everyone collectively worse off. I could talk about this for a while so I’ll stop here lol.

See “Tools for Life™️” , part 2 to this essay :)

All of this being said, I’ve also seen the negative consequences and risks of medication. My brother has described his ADHD medication as “narrowing his focus so much that he could only focus on one thing” — and for a long time, that one thing was anxiety that became so overwhelming that for many years it made it hard for him to be the best version of himself. He’s no longer on ADHD medication and describes his anxiety as ‘something that still happens, but now he gets distracted by something else before it can get too serious’. Choosing to be on medication is not a forever decision and is highly personal.

I write, ironically, at 4:02am.

A few months ago I got so overwhelmed by back-to-back social interactions that I became nonverbal. Yes, this was really weird for me, and no it’s never happened before (although I’ve pulled my brother out of this state in the past and it was interesting being on the other side). It felt like I had all the words to say but I couldn’t get my vocal chords or mouth to cooperate. Every time I was about to say a word or respond to a question it felt like I had just stepped up to a microphone in front of a huge audience — but couldn’t push past it to make a noise. I ended up pointing at things and… doing mime gestures. I’m pretty sure I did a completely silent mime laugh. Happy I got through it, will try not to overload myself so much in the future.

Environments that have helped me thrive have always been places where I can work intensely on the things that matter to me (ideally with people who care just as much), show up as the fullest version of myself, and not feel held back by artificial constraints. Examples have included my enrichment class (where for 5 years I got to do a yearly 4 month Independent Study project on any topic I wanted, presented in whatever format I wanted), SHAD (1-month team design project addressing a social issue), and Socratica (a community of people sharing & learning about all the stuff that gets them excited). We can absolutely create environments where highly sensitive people can find and support each other, develop resiliency, and thrive.

So many parts of this resonated with me + love how you reframe the diagnosis/disorder scale to sensitivity to the world.

One of my favorite things you’ve put out joss❤️

this was so very helpful and relatable?? such a relief to hear you put words to this why-am-i-so-sensitive syndrome. excited to read part 2!! thank you!